|  By David Jameson July 2013 | Art/Architecture | 9.5 x 11 inches The first biography of the infuential modernist artist and sculptor includes more than 350 full-color plates. |

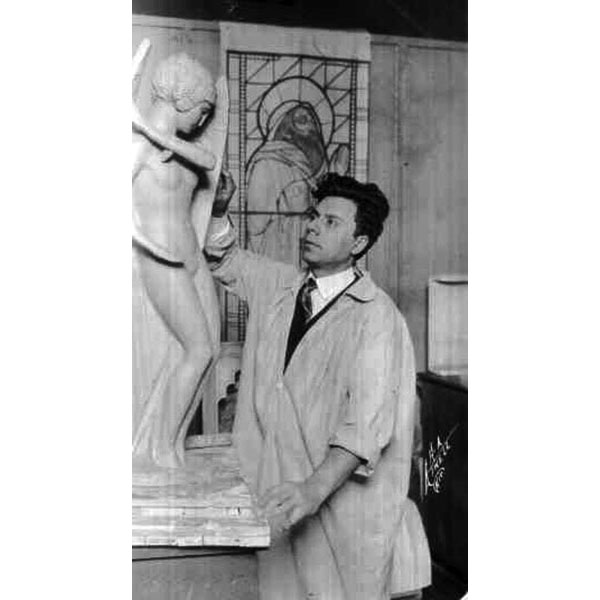

| Beginnings Born to a poor shoemaker in Andretta, Italy, Alfonso Iannelli studied the techniques of the traveling artists who stayed at his parent’s small inn. His father, Giuseppe, then set off alone for America to build a new life for the family. And in 1898, Iannelli, his mother, and two older brothers finally joined him in Newark, New Jersey, where Alfonso was soon apprenticed to a jeweler and, by 1906, to the famous sculptor, Gutzon Borglum. Alfonso Iannelli in his studio, circa 1925. |

He modeled figures for the new Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan before winning a scholarship to New York’s Art Students League. By eighteen, Iannelli had opened his own studio on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan and soon had moved west to Cincinnati and a job in a lithography company. Within the same year, he again headed west in search of the American Indians he’d dreamed of since his boyhood in Italy, eventually settling in Los Angeles.

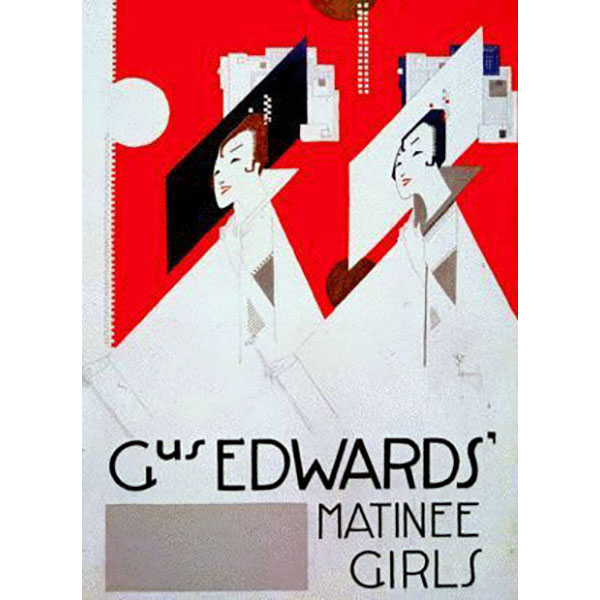

| Orpheum Posters 1912-1915 European Modernism and advanced advertising graphics first influenced Alfonso Iannelli’s vocabulary of illustration. He painted over one hundred lobby showcards for Los Angeles’ Orpheum Theater, later abstracting each vaudeville act into geometric bursts of color and shape. At twenty-two years old, Iannelli had already mastered a graphic and sculptural style in his commercial work that had yet to be utilized in other American forms of fine art. Orpheum Theater poster. |

Soon Frank Lloyd Wright was aware of his remarkable talent and invited him to Chicago for a collaboration that was to transform Twentieth Century architecture.

| Midway Gardens 1914 Working with Frank Lloyd Wright inspired Iannelli to create sculpture that was totally integrated into a cohesive, organic architectural artwork. Midway Gardens was Wright’s masterpiece of public architecture, a three-acre compound that integrated music, art, and nightlife. Through Iannelli’s architecturally expressed concrete figures, Wright saw the young Iannelli as a talented interpreter of his design language and a worthy partner to Richard Bock, his usual sculptor. Sprite for Midway Gardens, Chicago, 1914. |

Wright passed off all the sculpture as his own in the ensuing publicity, crushing Iannelli and depriving him of any credit in what could have been his triumphant Chicago debut. When Wright later asked him to create the sculpture for his Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Iannelli refused to ever again work for America’s greatest architect.

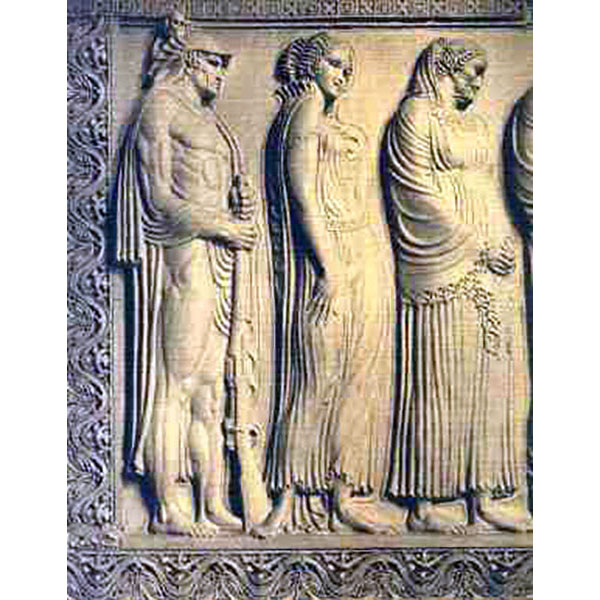

| 1915 - 1920 After sculpting for Wright, Iannelli moved permanently to Illinois and began working for architects Purcell and Elmslie, creating monumental sculpture for Sioux City’s courthouse, the Prairie School’s largest public building. Because he wasn’t a licensed architect himself, Iannelli also began a working relationship with his friend, Barry Byrne, a former draftsman in Wright’s studio. Their association allowed him to co-design entire buildings and complete interior schemes that propelled Prairie decor into a more modernist direction. Sioux City Courthouse, plaster maquette for entrance, 1916. |

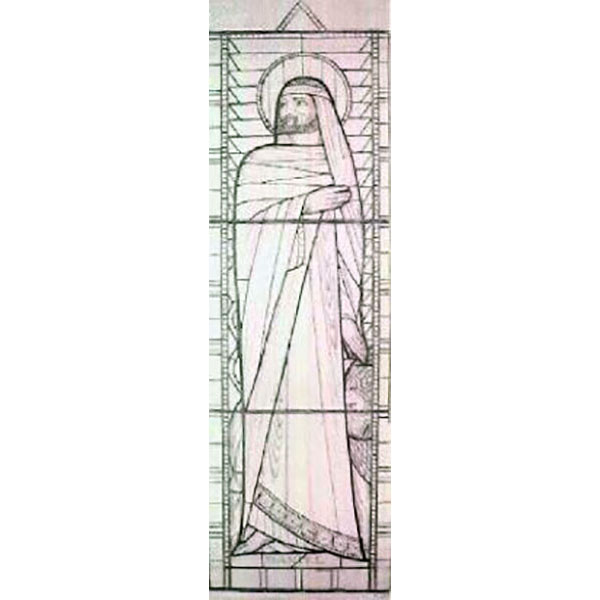

| 1920 - 1930 After establishing a commercial design studio in Park Ridge, Iannelli began teaching industrial design at the Art Institute of Chicago. He was featured in a group show at the Art Institute in late 1921 and early 1922, where he exhibited monumental sculptures, decorative items, and drawings of room designs. His modernist lamps and furnishings were so well received that the museum offered him a solo exhibition there in late 1925 and early 1926. Stained glass window. |

This showcased a large collection of his sculptures, fountains, designs for stained glass windows, and a stunning drawing of his proposed tomb for Louis Sullivan, the recently deceased godfather of the Chicago School. His collaboration with Barry Byrne led to important commissions designing sculptures and stained glass windows for churches throughout the Midwest. His modernist interpretations of Biblical subjects updated religious symbolism and transformed them into a contemporary language.

| Consumer Products Iannelli Studios grew rapidly with many new industrial and decorative clients. Artisans were hired to help him execute the models needed for consumer products and the decorative installations for movie theaters and retail exhibits. He had always insisted on complete control of advertising, logos, and branding for any client who came to him. And his skill at integrating all of the aesthetics made his finished product that much easier to market. Hair clippers design for Oster. |

His higher profile also made the Iannelli name into its own brand, and Sunbeam, Eversharp, Oster, and other manufacturers used it in their advertising to promote their advanced styling.

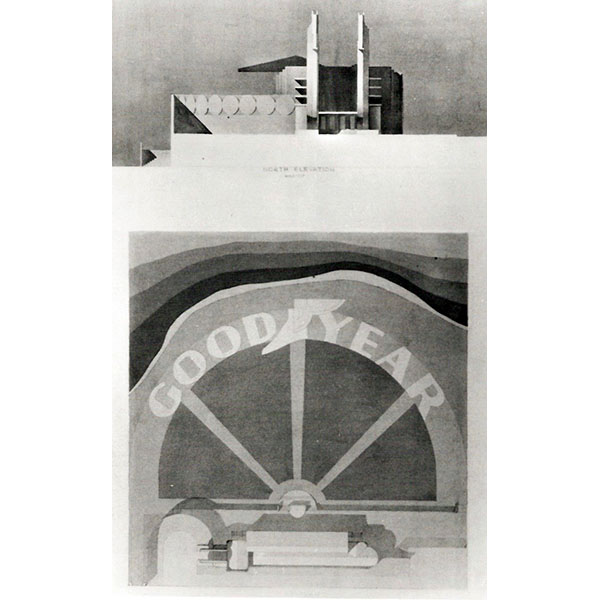

| 1930 - 1940 His design career included extensive work for A Century of Progress, Chicago’s 1933 World’s Fair where he was called upon to design an important entrance to Raymond Hood’s enormous Electrical Group pavilion. His sculptural friezes and streamlined facade for the Radio entrance ranked with the work of the fair’s director of sculpture, Lee Lawrie. He also designed, along with architect Charles Pope, the Thermometer Tower for Havoline Oil Company and a spectacular, unbuilt pavilion design for Goodyear Tire and Rubber. Goodyear Pavilion at 1933 World’s Fair. |

Other exhibit designs for the Enchanted Island amusement area, Elgin Watches, and Wahl Eversharp made Iannelli’s work for the World’s Fair a watershed event for his firm. The fair gave Iannelli his highest profile commissions and largest audience and his name was now known throughout the country. Iannelli Studios soon became the most successful commercial art firm in Chicago.

| 1940 - 1960 Iannelli’s patriotic fervor inspired his designs for wartime housing and public sculptures which were never built. He resumed his commercial approach with a simplified sense of style, perfectly in tune with modern tastes. His largest sculptural commission, and one of his last, was the monumental Rock of Gibraltar relief on the face of the Prudential Building, Chicago’s tallest skyscraper at the time. Rock of Gibraltar, Prudential Building, Chicago, 1955. |

| Iannelli’s Legacy Alfonso Iannelli came to Chicago in 1914 to sculpt Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Sprite” minarets atop Midway Gardens. The Art Institute of Chicago included his applied and industrial art designs in several exhibitions and gave him a one-man show in 1925. His attempts to start programs at Hull House and Art Institute for the teaching of industrial art finally found fruition in Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s curriculum at the New Bauhaus. Alfonso Iannelli, circa 1950. |

As an architect, sculptor, industrial designer, and teacher, Iannelli’s influence on graphic and applied art gave a fresh, modernist look to old forms and provided employment to several generations of commercial artists.

| Everyday Modern: The Industrial Design of Alfonso Iannelli This compilation from 2015 details the stories of his appliance and manufacturing clients to the 1950s. |

Click on images to view larger versions...

Rendering for unbuilt Goodyear Pavilion, 1933 |

Study for Orpheum poster, February 1915 |

Study for Orpheum poster, January 1915 |

Photograph of Pickwick Auditorium, circa 1929 |

Alternative rendering of 1933 Chicago World’s Fair “Radio Entrance,” circa 1931 |

Rendering of 1939 New York World’s Fair “United Nations Plaza Center,” circa 1938 |

Rendering for unexecuted Sunbeam toaster design, 1947 |

Pine carving of female nude, 1931 |

Design for unexecuted mural, circa 1915 |

|  |  |  |